More often than not, the market sizing slide in a start-up’s pitch deck is useless.

The problem is that founders view market sizing as as an exercise to strictly answer the following question(s):

Is my market size greater than $1 billion?1

If not, how can I make it greater than $1 billion?

When performed properly, market sizing is a powerful tool to help you better understand your business on a transactional level. Unfortunately, founders tend to be tunnel-visioned into backsolving for a value greater than $1 billion. Starting off the presentation with a clearly inflated market size will only make a VC more apprehensive and skeptical of what’s to come.

The Economics of Venture Capital

To understand the origins of the mantra, bigger is better, let’s start by examining the economics of venture capital.

VC funds consist of limited partners2 and a general partner3. Limited partners (LPs) contribute money to the fund and agree to not expect any distributions until after 10-ish years. The general partner is responsible for spending the money through a continuous process of sourcing, evaluating, and investing in promising start-ups. Unlike traditional public equities investors – who may hold assets just about indefinitely – VC investments are time-constrained and are made with the intention of exiting through either a secondary sale or IPO. After 10-ish years, the fund must fully liquidate its holdings and shut down, to provide a return to the investors.

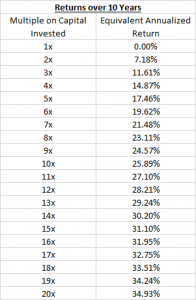

Given the high-risk nature of start-ups and long liquidity lock-up, LPs typically expect a 6x~ return on capital (equivalent to a 20% annual return)4. 20% a year is a lot. To put this number into context, the long-run annualized return of the S&P 500 is roughly 7%. How then do VC investors expect to return 6x+, especially when a majority of institutional equities fail to match the market?

The answer is risk. VCs take on significantly more risk than their peers in traditional public and private equities funds. Risk is heightened in the VC world because information is sparse. As a result, there is increased emphasis on the evaluation of external factors – like market sizing and competition – in early-stage investing.

What makes this even harder is that the distribution of returns is lumpy. A majority of investments in a VC’s portfolio fail or do not experience meaningful exits; roughly 20% of investments make up 80% of the total portfolio return. What this means is that it isn’t enough to simply target a 20% annualized return on each investment; the winners must significantly outperform to compensate for the losers in the portfolio.

In a nutshell – in the world of venture capital, when you win, you better win big.5

Market Sizing

So how do you win big? It helps to be in really big markets. An understanding of the true market size allows the VC to guesstimate the exit potential.6 There are two approaches to sizing up a market: top-down and bottom-up.

A top-down approach to market sizing requires you to estimate the total market size and a penetration rate. It is favoured amongst many for its simplicity and ability to generate larger numbers, but it offers little value to the investor. Unfortunately, the tradeoff for enhanced simplicity is a lack of specificity; total market sizes, identified through analyst reports, are often too broad and encompass products that are beyond of the scope of the start-up. Further, start-ups are innovative by nature and may produce solutions that do not fit neatly into existing market segments.

A more appropriate and informative approach is bottom-up analysis, in which market size is determined through an estimate of potential sales. At a high-level, this boils down to a simple formula:

Market Size = # of Target Customers * Average $ Value

When performed appropriately, the bottom-up approach is a valuable exercise that requires the founder to systematically think through each sale on a micro level, to understand and hypothesize the drivers that impact buyer behaviour. The challenge here is continuously breaking down each variable into mutually exclusive & collectively exhaustive components by assessing it against various factors. Considerations include (but are not limited to):

- Value-add for the target customer – will your product be saving time (and costs) or does it represent a new revenue stream for your customer? In general, additional revenue is valued more highly than costs savings, allowing for greater pricing power, which in turn drives average dollar value.

- Repeatability of sales – does the nature of your product lend itself to a one-sales business model? Or does a recurring subscription better match the flow of value? Repeatability drives average $ value upwards.

- Geographic reach – will there be barriers (regulatory, legal, or competitive) to expansion? North American start-ups typically target America for their beachhead entry. Increased barriers decreases the number of target customers.

- Market adoption – is your product a “nice to have” or a “need to have”? Are customers in your target market historically resistant to change? Lower historical adoption rates decreases the number of target customers.

It is important to note that this increased degree of specificity may not necessarily lead to a higher degree of forecasting accuracy. However, it will surely force you to think through your business and the market on a more granular level, allowing you to uncover novel insights and improve clarity in decision making. At the end of the day, the output of market sizing is a static summary figure; the real value of the exercise is the process.

While bottom-up sizing provides you with more insights into the business, it doesn’t hurt to run a quick top-down market sizing as a quick reasonability check. A significant variance between the two methods implies that your fundamental assumptions are not reasonable (in the bottom-up analysis) and/or the market scope is too broad/narrow (in the top-down analysis).

Competition

Understanding the competitive dynamics of the industry adds colour and also serves as a sanity check to the static market size estimate. It doesn’t matter if you’re able to spit out a large market size estimate if your product offering is poorly differentiated.7. Alternatively, if the market size is smaller, but your product is: 1) highly defensible with strong intellectual property, 2) a significant improvement in quality, and 3) a need-to-have given regulatory changes and/or industry economics, then a smaller market size is more palatable.8

Other things to consider include:

- Degree of fragmentation – it’s possible to have incredibly large market sizes with a high degree of fragmentation (think: fast food restaurants). Does the high degree of fragmentation imply commodification of the product/service? If so, is this going to be a painful race to the bottom, where you’ll compete on the basis of price? Or is your start-up going to capitalize on the fragmentation by bringing about a marketplace to enhance liquidity?

- Incumbents – large markets are also likely to have large players with deep pockets and long-standing customer relationships. Is your product a nice-to-have or a need-to-have? Are the switching costs high in this industry? Are the incumbents in a position to replicate your unique offering? Or are the incumbents blinded by the innovator’s dilemma, making this a prime opportunity for your start-up?

As you can see, competitive analysis is a more dynamic process that requires the guesstimation of a competitors’ future activities. Bundling the insights from competitive analysis with the static output of market sizing paints a clearer picture of the attractiveness of your start-up.

Parting Thoughts

The next time you bring your deck to a VC, optimize for accuracy and reality. Excessively optimistic forecasts and projections will only raise a VCs guard and impair your credibility as an operator.

You should view your first meeting with a VC as the start of a relationship and not just another transaction. And if you want the relationship to go swimmingly, it helps to have a foundation built on trust. Just remember, honesty is always the best policy.

TL;DR – Bigger isn’t always better because:

- Market size estimates are a static abstraction of a dynamic environment. Undesirable competitive environments can quickly overshadow seemingly impressive market sizes.

- A focus on artificially inflating market size in bottom-up analyses takes away from the true value of such analysis. When it comes to market sizing, it’s more about the journey rather than the destination.

- Data isn’t considered in a vacuum; investments are not made by simply checking off the requisite boxes. Rather, a holistic approach is adopted that considers various data points are in relation to each other, in order to best paint a picture of the company’s future.

- For some reason, the industry as a whole seems to have settled on $1 billion as the absolute minimum market for venture funding. I’m not entirely sure why or how this happened, but this myopic view is the reason why market sizing slides are generally all but useless.

- (people with money)

- (people who do work)

- For the sake of simplicity, calculations are made before considering fund expenses and incentive fees

- This is really crucial to understanding the VC decision making process. The need to return significant multiples on invested capital, in a nebulous, high-risk environment, is the reason why the demonstration of traction and product market fit is key in early-stage investing. It isn’t as simple as identifying under/over-priced assets. The corollary is that you can have great businesses that aren’t a fit for VC funding. Before drafting your first pitchdeck, evaluate the needs and nature of your business and consider whether other sources of financing are more suitable.

- In the startup world, valuations are typically performed on the basis of revenue multiples. The high degree of estimation uncertainty makes it challenging to apply discounted cash flow analysis or other intrinsic valuation methodologies.

- If this is the case, you might want to review your estimates of market penetration and revenue build-up. This might also be a sign that venture funding isn’t right for your business.

- This tends to be the case with medical device start-ups.